By Michael Knox

Mknox@modernfilmzine.com

Jesse V. Johnson has made a career performing stunts in movies such as the new Michel Gondry directed “The Green Hornet” and Tim Burton’s “Alice in Wonderland.”

But while he’s earned most of his paychecks in front of the camera as a stuntman, Johnson is steadily building a career behind the camera as a director.

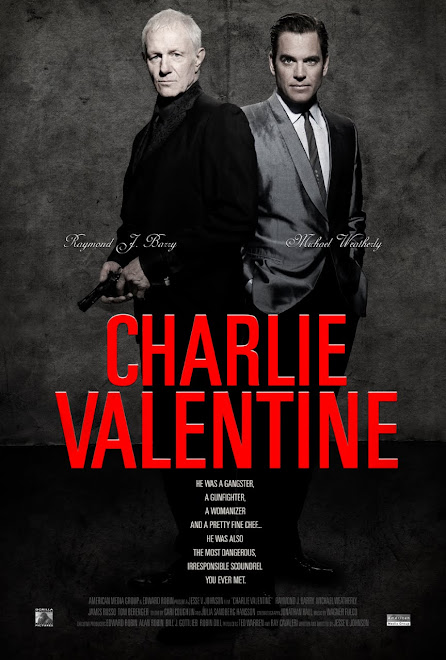

Johnson’s latest film, “Charlie Valentine” is a father and son family drama, disguised as a mobster movie. When Charlie Valentine pulls a heist that goes wrong, leaving his crew dead, he goes to hide out with his estranged son. There the story grows as the two reunite and get to know one another.

Notable character actor, Raymond J. Barry plays the lead character, “Charlie Valentine” with television’s “Navy NCIS” actor, Michael Weatherly starring as his son, who also wants to get more involved in the mobster scene.

Johnson worked with Weatherly and Barry on “Charlie Valentine,” but has made a career of being on movie sets even before getting behind the camera, thanks to his time as a stuntman.

Johnson has now performed stunts in more than 30 projects, including “Avatar,” according to the Internet Movie Database, and has directed nine films so far.

“The two jobs have always been interconnected for me. One didn’t lead to the other, so much as finance it and fuel it and motivate it,” Johnson said. “I love doing stunts. I love watching great directors at work. I left school very young, and stunt work has been my college and my film school, believe it or not.”

Johnson’s career helped give him the education he needed to film “Charlie Valentine” in less than a month. He shot the movie in just 18 days using, for the most part, a single location that doubled as different sets for the movie. The movie was shot in and around Willow Street Studios, downtown Los Angeles.

“Shooting this way minimizes transportation and driver costs, and really just makes things a lot easier. You have to be imaginative with your set design though,” Johnson said. “Look for the round concrete columns. They drove me mad. They’re in the strip club, Danny’s apartment, Rocco’s warehouse, Ferucci’s office. They are part of the structure but we had to keep hiding them, it was very frustrating. But the ease that shooting at one location brought was invaluable to this shoot, it just wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.”

Johnson is already planning his next movie, but sat down with ModernFilmZine to discuss his career as a stuntman, his work on “Charlie Valentine” and his memories of working with Raymond J. Barry and Michael Weatherly.

1. How did you first get involved in filmmaking and how has your career developed to allow you to work with the level of talent you have in “Charlie Valentine?”

“I was always a story-teller. My mother would rent a super eight movie projector for my birthday parties, and it was my favorite present. This was when a VCR was something only wealthy families could own. It sounds awfully quaint now, but it wasn’t so long ago, really.“

“Cutting ahead to the second part of your question, really it is the script that counts when you have less money to offer. ‘Charlie Valentine,’ was a script that excited managers and agents, and was thankfully passed onto clients. And Ted Warren, our casting director, was relentless in his pursuit of interesting names. We fought a lot, but it was good to have a collaborator like that. He should take a lot of the credit for the exceptional cast.”

2. What made you decide to do a gangster story to begin with?

“When I wrote the script I was at the tale end of a fantastic romance with French gangster movies. My wife and daughters and I had spent a Summer traveling around France, and I truly love that country. I found an old book on French Gangster movies in a brocante in Miropoix. The black and white pictures were really the initial inspiration, that and a personal story that was somewhat similar to the one Michael Weatherly goes through in the movie.“

“But then you always steal from your personal life. Ask any other writer. We’re the ones who listen during conversations. We steal, acquire and borrow from real life. Movies that borrow from other movies too much, tend to suck. I try to stick to real life. Of course that means you actually have to live life, too. Sometimes that can be hazardous, but the books and movies I love were written by men and women who put themselves in harms way.”

3. What made you decide to then weave that with the father and son reunion aspect of the story?

“I tended not to think of this as a gangster movie. Of course it falls into that genre, but as I wrote it, I wrote it as a love story between a father and son. The father is a rascal and a bit of a character, the kind of fellow who detests growing old, waking up alone, or actually having to work for a living. That might make him a gangster, but I feel it also makes him exceptionally easy to identify with.”

4. What were some of the challenges directing this script provided you and how did you overcome them?

“Well, the film did not have a studio sized budget or shooting schedule, and that brings it’s own challenges. We shot in one location for 17 of the 18 days. That was tricky, making sure it all seemed organic but different was a great challenge to Terry James Welden the production designer who is excellent and very, very creative.”

“ The one day on actual ‘location’ was an interesting exercise. Half the crew and the Cobra car (editor’s note: Charlie Valentine drives an antique Cobra in the movie) got lost trying to find the filming site. It’s funny looking back, but was sickeningly nerve wracking at the time. Basically I was very lucky, in that my executive producer, Edward Robin, was exceptionally generous and supportive and really just had great faith in my vision, my ideas, and backed me in every fight. You can’t ask for anymore”

5. What tips do you have to filmmakers getting started and what are some lessons you learned with “Charlie Valentine” that you can pass on to filmmakers getting started?

“Artistically, you must trust your instincts.”

“It is an incredibly personal thing, but while making the actual movie, try to shoot it at as few locations as possible. This allows you more time to focus on the work. Make sure the script is right before you start, this means harsh criticism, loving criticism, brutally honest criticism.”

“Do not start until you and all of your partners feel it is ready.“

“Finally find a great crew, and a great cast. Try to find supportive players, look into their eyes, try to assess their motivations, make sure they are in line with your own, not necessarily the same, but in line, and headed towards a similar final goal.”

6. What were some of the most interesting scenes for you to shoot on “Charlie Valentine?”

“I loved shooting the scenes between Raymond J. Barry and Michael Weatherly. I was so excited to photograph them together, they were so enormously gifted in their own ways, you really had to just point the camera and not screw up technically.”

“We would shoot the scripted scene, get it right, then improvise and try alternate ideas, until we felt we had the heart of the scene captured. Sometimes it stayed very faithful to the written word, other times we went in another exciting direction all together.”

“Raymond would do things, little things and I’d have to try to spot them and capture them, it was exciting and wonderful. Michael was a lot of fun, too, he brought a natural spontaneity to the character, to the scene, that was exceptionally refreshing for me.”

7. One thing I noticed in the film, was your use of the razor blade that Charlie has. It’s used to kill, but is also used to gently shave his grown son. For me, this one object showed the dual sides of Charlie’s personality. Was that a conscious act, or am I placing more importance on that then you intended? And if it was conscious how did you develop that angle, and what are some other things I might have missed that you used?

“Charlie is the razor blade, yes! I like that, although it’s an imperfect metaphor, because Charlie is not a benign character who then becomes dangerous, but the other way around.”

“The razor blade was an important part of English gangster lore. I was obsessed with the writing of Graham Greene as a child and was always going back to the slashing scene in ‘Brighton Rock.’ Really a razor is a terrible choice of weapon. You have to get close, really close, closer than with a regular fighting knife. It is the opposite of practical, but that’s what’s interesting about it.”

“There are other uses of visual and dialogue symbolism in the film, but, really if I have to point them out, I feel the film is failing, and left subtle, they are better absorbed, I think.”

8. What’s one of your best anecdotes/stories you have regarding working with Raymond J. Barry? And how did your working relationship develop with him?

“A young actor came in and started discussing the dialogue. Now, I’m always open to this, and actually enjoy a bit of give and take. It’s creative and alive, and fun, and usually yields good results. Raymond was sitting on the edge of the stage and I could see his body language changing, physically changing, getting more angular, irritated even.”

“The young actor was firing away suggestions, and they were getting a little wild, but not out of control by any means. He worked himself up a bit and turned to Raymond, who had his back to us, by the way, and asked, ‘What do you think if I say this…?”‘”

“Raymond was awkwardly silent for a long beat, then stood up very slowly, like a dramatic actor in a Greek tragedy. He turned to the young actor, looking down on him, through his imperceptibly slatted eyes and said in a low growl, raising the script in his right hand, somewhere between granite over gravel and chipped flint – ‘I signed on to play this character, in this script, and I intend to say the dialogue as it was fucking written.’”

“He stood absolutely still, not taking his eyes off the actor. I knew I had cast correctly at the moment, and I couldn’t help smiling as I calmed the young actors nerves. It was less a statement, as we of course played around with line changing on a daily basis, but a test of that young actor. He was auditioning the actor!”

9. What was your working relationship like with Michael Weatherly?

“Michael was just fantastic. You couldn’t wish for a more supportive, friendly, upbeat team player. He knew his character backwards, not a great deal of discussion, not a lot of agonizing, he went for it and enjoyed himself. But always careful, considerate, and artistic.”

“I do know the females on the crew would look extra made up and particularly well groomed whenever Michael was working. Strange, no?”

“He reminds me of a young Clint Eastwood in looks, I’d love to work with him again. I don’t know why he plays the fool on his TV show, and I do like him on it, but, he has so much more to offer as a leading man, he should be carrying major movies, I hope he does soon.”

10. What are some of the challenges “Charlie Valentine” faced with distribution?

“Sure, you can make films cheaply now with all the micro technology, but it is harder than it has ever been to make a profit, and this is what is killing the B-movie and it’s a real shame, but it will sort itself out.”

“Part of the problem is there is no tactile interaction anymore, you don’t go to stores and look through titles, you get your internet titles suggested to you by your download agent, someone controls this list, and it is decimating the market.”

11. Any other projects planned that you can talk about?

“Yes, I am returning to my more action oriented roots. I am bitterly frustrated by the state of action cinema, and feel more than ever it is time to shake things up.”

“Also, great action will be a way for me to compete with the majors. I just cannot afford to or seem able to get onto the radar of the major agencies, the agencies gate keeping the A list talent, and without an ‘A’ list name in your movie, you are relegated to the world of straight to DVD.”

12. What kind of research did you do for writing “Charlie Valentine?”

“My research is always a great fun part of the ‘job.’ I’m sure my computer IP address is listed on every federal agencies database —- Chicago Underworld, stolen electronics reselling, parole violations and officers protocol, knife fighting, wounds with razor blades. Killers who used razor blades.”

Johnson continued to discuss his research just on “Charlie Valentine,” adding more details he stumbled across.

“The correct way to shave with an open razor, a Mexican barber in the San Fernando Valley actually, this was quite enlightening to me and enjoyable. Cigar aficionado techniques, wound ballistics, images of men killed with blades, revolvers and shotguns. Opera translations and history, this was fun and I am a huge fan of opera music so it was really just brushing up on it.”

Johnson talked about how some information can be helpful for developing specific characters.

“I had worked with some strip club managers on another film ‘The Butcher,‘ so knew them quite well, and used some of their intimate language with Steven Bauer’s character.”

Johnson said his research also helped with fleshing out Raymond J. Barry’s performance as an old school gangster.

“I enjoyed watching a specialist show Raymond how to draw, reload and shoot his revolver in the manner of the old timers. It’s quite different to how they do it today. I brought in a character I’ve known for some time to chat with Raymond about actual knife fighting techniques and some of the things that might happen in real life.”

13. Any real people you borrowed from to flesh out the characters in “Charlie Valentine?”

“Over the years, I’ve been lucky enough to have run into some real characters, men who truly live life by the second and who are uncompromising and honest to their ideals. I respect and actually envy them, they couldn’t get a movie made with their attitudes, but they have absolutely no interest in making a movie anyway. The amount of groveling, self emulating and ridiculous game playing would drive them nuts. They’d just walk away or shoot someone.”

“I enjoy these kinds of characters company (men and women by the way), and I think they put up with my questions. Whether society views them as heroes or villains, I believe they are important to us as a species. I like films about these kinds of men and women. I’m not really interested in films about nerds or geeks, there are great films being made on those subjects, but not by me.”

“Iconic characters, are rare, and inspirational, and I seek them out in literature and real life. The most obvious fictional character I borrowed from for ‘Charlie Valentine’ was Bob from, Jean Pierre Melville’s film, ‘Bob Le Flambeur.’ Otherwise the characters were based on real life as much as possible.”

14. What was the funniest moment you had filming “Charlie Valentine?”

“I was terrified, scared, exhilarated and downright panic stricken. I think it’s probably too soon afterward to ask about amusing moments, but I’m sure there were many.”

“I remember laughing a lot with Raymond, who has a very dry intelligent sense of humor. My crew seemed to always be smiling, but it’s very stressful, and events often aren’t immediately funny, per se.”

“Dominiquie Vandenberg always makes me laugh. He is a great friend and a supporter. Vernon Well’s hat in the movie made me laugh. It was a big black Russian bear skin thing. I have no idea why he chose it, but he wouldn’t budge and believed it was very much in character, but I giggle every-time I see it.”

15. Do you have an inspirational story for young filmmakers reading this regarding your work on “Charlie Valentine?” Was there ever a moment that you thought this movie wasn’t going to happen and you found a way to make it work? And if so how?

“Right up to the moment you step onto set you have that awful thought in your head, that everyone is going to be let down, there will be an awful admission by your financiers there is no money, everyone should go home.”

“I get it every movie, every goddamned time. You just have to bury it and continue full throttle ahead, not holding anything back, go for broke, put it all on black, cry Harry for England and Saint George!”

“2009 was my worst year ever, I had three huge projects implode, during casting and location scouting, I had a crew in Utah working for a month, that wasn’t paid, it was dreadful. I was in terrible shape financially, winning awards all over the world with ‘Charlie Valentine’ (at one point one a weekend for five weeks straight), but those don’t pay.”

“It’s a brutal street fight of a business, not for the squeamish, but when it clicks and goes right, brother there’s nothing like it, you’re in the company of Gods!”

16. Prior to filmmaking what did you do and how did that career lead you to writing and directing movies?

“I was always writing, however, I was an army cadet and a reserve, then I volunteered for commando school, where I was beaten senseless by a sergeant called Valentine.”

“I wasn’t considering getting out, but my uncle who is a successful stunt coordinator (Vic Armstrong), saw me in miserable shape and called me a ‘fucking idiot’ – he said I should come to work for him.”

“I went off to Mexico City, at 17 years old and did some stunts on Paul Verhoeven’s, “Total Recall.” I used the money I made there to back my first short film. I’ve been alternating between the two jobs ever since and have found a peaceful, and excitingly rewarding way to make it work. I’m really very, very lucky!”

17. What are some things your career as a stuntman taught you that helped you in working on “Charlie Valentine?”

“Obviously stunts and special effects protocol, what is and what isn’t safe or achievable. Although, I like to throw the unachievable at my stunt team to see what they come up with.”

“Most importantly, the ability to work with actors, to calm them, listen to their concerns, to get over the initial panic, that the person in front of you is your hero from a dozen movies, to show respect, but at the same time, listen to a worried, concerned artist.”

“I learned to love and respect the work that these people do, and what they do is incredibly difficult. Every so often I throw myself into someone else’s movies, give myself a talking part, and good lord I panic. It scares me to the very core of my existence. There is nowhere to hide no way of cheating it. These guys go through that every job they take. I love them for it!”

18. I saw that you did stunts in “Alice in Wonderland” and “The Green Hornet” can you talk a little bit about your work on those projects? And what can fans expect to see from Michel Gondry’s interpretation of “The Green Hornet?”

“I’m really not comfortable discussing those sorts of things. I know Garret Warren who coordinated ‘Alice’ is a genius and a very talented coordinator, he does most of my films, and I continually learn from him.”

“Vic Armstrong who directed the action in ‘The Green Hornet’ and ‘Thor,’ is a veteran and one of the most skilled action choreographers who has ever worked in the business. Watching him is like being a part of the most elite form of post-graduate film school study imaginable.”

“I also steal blatantly from him all the time. In 30 years plus of doing what he does he has rarely, if ever, consciously repeated himself. What a rare work ethic.”

19. What were some of the craziest stunts you did for “The Green Hornet” and what are some of the craziest stunts you’ve done in your career?

“Really, and this is a boring answer, the crazy stunts are the ones to avoid. You try to make something look crazy without endangering yourself or the crew. No one, not the director, certainly not the producers wants an injury or worse on set.”

“You’re job is to make it look dangerous. You have to be smart, calculating, rehearse a lot and be disciplined. The age of the gung-ho bone breakers is over.”

“People get upset at the sight of blood on a film-set. That said, my heart has raced a few times, and seeing your own broken bones protruding from your flesh is a grounding experience.

20. Is there anything you wished I asked you that I didn’t think to ask you that you would like to talk about?

“I should probably say that we had an incredible crew of committed young filmmakers, an excellent line producer in Kelli Kaye, and that truly the film would probably not have happened without this addition to the creative pot, of cast and script. A film is made by a lot of heads all thinking as one

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)